The Corresponding Secretary recently received a laconic message – a note scrawled on the back of a band flyer, but more oddly still, neatly folded and stamped in an envelope. The note states that it would behoove the editors of Communiqués to have read a short story titled “The Beak Doctor,” written by Eric Basso in 1977. Beyond a polite intro and outro, this is all it contains.

We have read the story, and have a few comments to make.

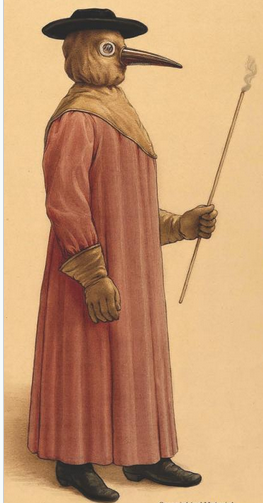

The early modern entities known as beak doctors were plague doctors. As the black plague ravaged the cities of Europe, those hired by municipalities as plague doctors – often at great trouble, and with elaborate contracts – often wore a kind of hazmat suit to make his rounds. Here is one description of the costume:

“Attributing the disease to corrupt vapours, the physicians protected themselves by means of suits of leather, with large crystal glasses and a long snout containing aromatic spices, employing also a wand with which to issue instructions” (“The Plague Doctor,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, Vol. 20 Issue 3).

[Cover art for Marc Estrin, The Annotated Nose. Unbridled Books, 2011.]

The foul vapors or “miasma” believed to be responsible for spreading the plague filled the role later held by germs in the medical and hypochondriacal imagination. The beak in the beak doctor’s costume acted as an air filter, being stuffed with substances and materials understood to prevent the plague-particle-bearing miasma from reaching the nostrils, by overpowering it with stronger aromas: lavender, sage, rosemary, mint, camphor, dried flowers, garlic.

The beak doctor was avoided like the plague, as it were, by the healthy, and was expected to live cut off from ordinary society. Those commissioned as beak doctors were also frequently empirics – which is to say, lay practitioners who believed in the virtues of observation and experience in medical practices, rather than in studium. Now, aside from the fact that members of the Order of the Third Bird, by a short stretch of the imagination, could themselves be called empirics, lay-midwives of experience; and aside from the fact that they frequently engage in the self-isolations of ritual; or to take it further, that the protocols of the Order could be considered prophylactic in one or more ways – what exactly did our correspondent have in mind with his literary recommendation?

[Cover art for Stephen Massimilla, The Plague Doctor in his Hull-shaped Hat. Stephen F. Austin UP, 2013.]

Here is the opening paragraph of Basso’s text:

“Now I will try to keep awake. The fog. They must have come for me before morning. Empty streets. Across a dimly lit room. She lay in the shadows. The steps. One at a time. Not that I’m old. It was the mask. Plaster chipped off the walls. She lay asleep on a couch. A network of cracks and branching veins like the surface of an antique painting. Chiaroscuro. Figures half formed…. .”

There are several things to point out here. First, the plague in this story is not the bubonic plague but a kind of sleeping sickness: one falls asleep and never wakes up. The cities of the sick are blanketed and blinded, as well, by a thick fog. There are no longer landmarks or destinations, only things stumbled upon by chance. In the fragmented articulation seen in the passage above, it is almost as if this fog had infiltrated the narrative itself, transforming it into mere gasps and glimpses of meaning, just as the fog reveals only what is closest. The world is reduced, both by the fog and the diction, into a series of “macroscopic vignettes.”

The beak doctor, in Basso’s story, carries a penlight, prescription pad and vials of penicillin instead of a staff, but the accoutrements of modern medicine are as useless to him as bloodletting would be. Moreover, his mask doubles the effects of the fog and the disarticulated language. Through the small eyeholes, everything he sees is isolated and framed; everything becomes an image without ground or context.

[Paul Fürst, engraving, 1656. From Wikipedia Entry, “Plague Doctor.”]

It is possible that our correspondent wished to indicate to us what Bird-like acts of attention might look like in a Gothic mode, which is to say as a series of acts of adaptation and survival in a world rendered labyrinthine, fragmentary, uncanny and miasmatic – or perhaps a series of acts that render the world labyrinthine and mysterious, vignettes pearled out along a tenuous thread, each an enframing that makes what is seen and sees what is made.