We have recently received word that an associate of the Order of the Third Bird, known as Martin-Pêcheur or Kingfisher, has completed a journey along the medieval pilgrimage route known as the Camino de Santiago or the Route of Santiago de Compostela (or in French, Saint Jacques de Compostelle) – the route of the “field of stars.” What is most extraordinary is that on his way, he was able to find and join gatherings of other Birds, and participate in Actions of sustained attention to the precious objects and works scattered along the route as in a starry sky; and not only this, but was able to uncover the long-lost story of a goldsmith Bird, reaching out into the past, in an act of historian’s attention, to unify a scattering of facts into a new constellation. For some time the details of the creation of the goldsmithed reliquaries and treasures of Sainte Foy, in the village of Conques on the Compostela route, had been obscure – and as it so often happens, we can see that this story is caught up in the tangled history of the Order, whose traces our correspondent seeks. Here are his words, modestly translated by one of our editors.

Chronicle of a Bird-Pilgrim

Birds of the Order know ways of making themselves receptive to legends that are told about others of their kind. Among the histories relayed by oral traditions, it often happens that the members of this very discreet Order bestow something of themselves to posterity through the play of symbols, and that their presence and their labors reach us, across time, to be grasped only by those who have ears to hear. Having on numerous occasions heard the joys of the pilgrimage road of Saint Jacques de Compostelle evoked, I could not help but recall certain of the little details that persisted across these testimonies.

Several of the legends relate certain odd behaviors assumed by Birds, for example the following:

Until the last century, there rose in the middle of the bridge [at Le Puy-en-Velay] the statue of Notre Dame du Puy, standing witness to the links of the Compostelle pilgrimage to the great Marian sanctuary of Puy in Velay. Now, according to the legend, a little bird would fly up the river, wetting its wings in flight, in order to bathe the visage of the Virgin, and all living there saw in this a sign of abundance and prosperity. Alas! Victim of the indignities of the years, the statue, very damaged, was transported in 1846 to the San Pedro church, where it is known by the name of the Virgin of the “Chori” (bird) or “Txori” in Basque. But since that year, the little bird has never appeared again.” (Translated from Patrick Huchet and Yvon Boelle, Sur les Chemins de Compostelle, Editions Ouest France (2014)).

It did not take much more than that for me to undertake to prepare for a Compostelle pilgrimage, for it did not appear to me impossible that the Birds, from near or far, had traveled these routes and Practiced on the way. Although from the beginning I encountered signs of the possible presence of Birds – numerous sculptures representing birds, and this from the moment of departing Puy en Velay – I will not tell the story, however agreeable it might be, of my first ten days of walking those fields and forests whose beauty little by little soothes those who tread and traverse them. I will begin, rather, with the story of my arrival in the celebrated town of Conques, an important stopping place for the pilgrims of yesterday and of today.

The beauty of Conques is unanimously praised. The town was evoked already by the poet Ermold le Noir in a poem whose content gave me great hope as to the new signs that I hoped to find:

Formerly this place, harsh and rugged as it was,

harbored only the savage beasts and the birds,

who filled the valley with their melodious songs.Translated by Hannah Green in Little Saint (Modern Library, 2001).

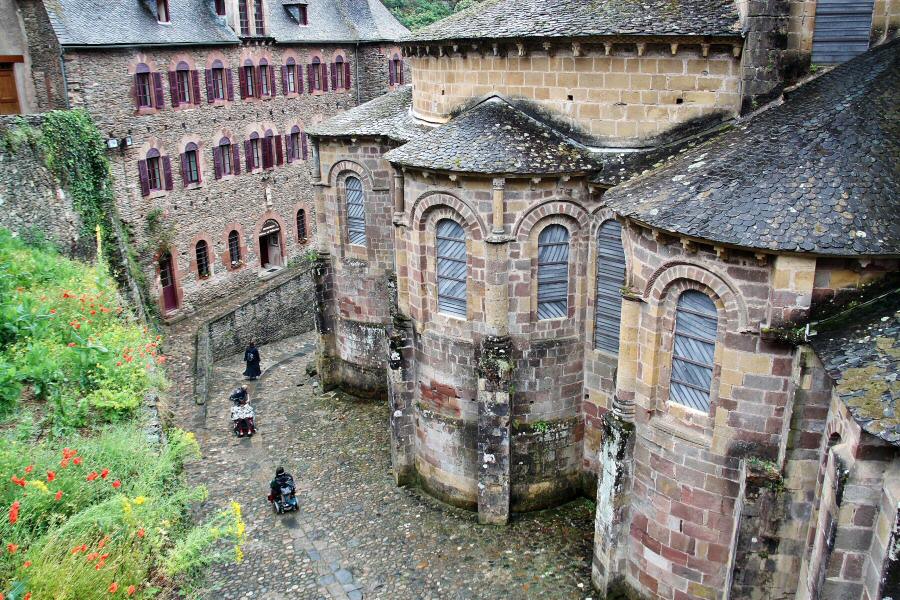

One arrives at Conques as if falling upon a nest, and especially for those on foot, the town only begins to appear as one descends into the hollow of the valley between two abrupt slopes. The hidden village takes its name from the shape of this hollow in which it was built,resembling a Saint-Jacques shell (or king scallop), which always reminds me of spread plumage, its feathers composing a gracious fan.

The grand abbatial church of Conques carries itself like a treasure in a jewelcase, and one can walk all around it upon the village’s various elevations, while remaining very close to it. In this way one has the impression of flying freely around its imposing architecture. The place is ideal for states of contemplation, and seeing it I better understood – and later, better still – the painter Pierre Soulages who created the stained glass windows of the abbatial church and who writes: “Conques is where I experienced my first artistic emotions.” After wandering the village in search of signs and evidence, and interrogating several of the monks who welcomed me to the Abbey, I was advised in mysterious tones to cast my eyes upon the treasure in the abbatial church, which I did.

“Rare and remarkable,” “splendid and marvelous,” “astonishing, fascinating, mysterious, even enigmatic,” not to mention “unique.” Over time, descriptions of this treasure have become an admiring litany. The relics of Sainte Foy are contained in goldsmithed pieces of a rare finesse, and upon which one beholds, in their enchanting beauty — birds. After some drawn-out moments of observation, I asked the guide if the artisan of such beautiful pieces was known. He responded then that the donor of the relics was known, and their sponsor, but not the one who had forged them such beautiful enclosures. The Book of Sainte Foy itself has had several of its pages torn out, those concerning the realization of the works conserved at Conques. The only mention of the artisan is found in another chapter of the work and must have been forgotten by those who wanted to rub out its traces: the name of “Noddy, the blacksmith of the field of stars,” concealed among its lines. I could not but be arrested by the name of this mysterious blacksmith, since he bore the name of a bird. Convinced that this was here proof sufficiently solid to carry my researches further, I contacted a Bird of the Order for assistance in exploring to this purpose the documents contained in the prolific W-Cache, well known to students of the Order.

While I was waiting for the results of inquiries, my travels continued. But it only took a few days – during which I came upon no more signs, but began to understand the bewitching perfection the art of this blacksmith had attained – for someone to contact me.

Some pages of a manuscript strongly resembling the manuscripts I had consulted at Conques were, in sooth, found in the W-Cache. Unfortunately, they were almost illegible – although below is a reproduction of the parts of the text we were able to read at the cost of a long labor of decipherment of Latin graphs and medieval abbreviations. After several months of research, a true encounter became possible with the mysterious blacksmith of the field of stars whose discretion when it comes to the things of this world is equal to the excellence of his artisanship.

Master Noddi was not only one of the greatest artists of our time, but his heart had been refined in the fires of long years walking the paths toward the holy city of Santiago de Compostela. This artisan accepted – though not without hesitation, given his habitual humility – to realize the pieces asked of him. In exchange he made several astonishing requests, which nonetheless were not of the sort to trouble the unfolding of his work; they were granted him.

{…}

The first piece is finished. The Sainte Foy in Majesty is a marvel of goldsmithing. The statuette measures 85 centimeters in height. It is made of yew wood covered with gold, gilded silver, and enamel, and set with gems that enchase the skull of this Carolingian majesté. I cannot find the words to describe the unbelievable beauty of this work.

As previously agreed, a group of unknown men and women were seen to gather around the reliquary after its creation. Numerous guards were of course present to assure themselves of the intentions of these visitors, who remained a long while fixedly and silently observing the reliquary. I do not believe I recognized the prayers they enacted, but I do trust the artisan with regard to the significance of such a gathering. The group then left the grounds and drew away near a great oak tree which offered them shade during a conversation the context of which was never communicated to me.

{…}

The collection is completed, with neither delay nor any disappointment as to the exceptional quality of its working. It is composed of a hexagonal reliquary; a pentagonal reliquary; the famous “A of Charlemagne”; a chasse, a Crucifixion plaque, a lantern in the form of an antique tomb, an enthroned Madonna and Child, a Pope Paschal reliquary, a reliquary tryptich and a reliquary arm of Saint Georges. Before Noddi once again took up his journey and his guests dispersed, I was invited to strange ceremony which, I imagine, is a rite transmitted from artisan to artisan. Since our man has mastered his art to perfection, I decided to pay my respects at this occasion which could not, I believe, do any harm to the diligent conservation of the Holy Relics.

{…}

We observed four silent phases of which I cannot be sure of the length, and which I describe below. The first phase consisted of considering, before all, the space that welcomed to the receptacles created for the different relics, and illuminating in one’s thought the fires of the forge, preparing to submit to it all their materials. The second phases required an attentive observation of the work, a total and unconditional acceptance of it. A third phase was consecrated to a kind of decomposition of the work, into the various forms of matter that composed it, rendering to nature, which had produced them, the minerals and precious stones used for its creation. Finally, the fourth phase demanded a consideration of the work as if each of its forms, its colors and its materials possessed the force and beauty of a celestial work, and thus to cultivate in oneself the greatest astonishment and the grandest admiration for it.

I must say that despite my initial reticence, the experience was of great interest, even if I do not believe I have gauged its fullest amplitude, lost as I was amid my thoughts, which assailed me without cease while the other participants seemed so profoundly absorbed in the activity of contemplation. However I sensed being born in me a curious relationship, dense and vibrant, with this piece of goldsmithwork. Several times I thought I saw the door come half ajar which might lead to a full understanding of these objects, as if I were about to enter for the first time into the heart of things. But these fugitive sentiments were extinguished as quickly as they appeared.

—Amaury de Rugis, Scribe of the Abbatial Church of Conques

It is not impossible that it was the witness of this Practice himself who sought to withdraw these passages from the final manuscript of the Book of Sainte Foy, so as not to risk being accused of paganism. It might also easily be that a migratory Bird deliberately safeguarded, in this way, the discretion of the Order. In this way it is now added to the practices and protocols now conserved in the archives and will, I hope, utilized by its contemporary inheritors. In the meantime, research on the goldsmith of the field of stars can only continue and be documented by other students (or members) of the Order who undertake this pilgrimage and who find on their route other signs and wonders leading to a better understanding of this remote forebear of the Order.

—Kingfisher

The Protocol of the Forge: Kingfisher’s Reconstruction

Rekindle the forge.

Sense the elements and the materials around and in the work and envisage their response to the fire of the forge.

Awaken the work.

Observe the spark of life that the work has been given, its open presence to the world, its existence, its breath.

Decomposition.

Decompose the object into its different constituents and imagine that each returns, in its original form, into the mines, the rivers, the forests or the quarries from which it came.

The matter of stars.

Imagine that the work is made of a precious metal, a fragment of a meteorite or of a star with extraordinary properties; embrace its strange, alien, and magnetic power.